A laborer working at a construction site. — AFP/File

#Pakistans #construction #sector #losing #ground

Lahore: Pakistan’s construction department stands at a confluence. With large -scale infrastructure projects, from road networks and dams to urban development and special economic zone, either ongoing or planning, the potential for development is sufficient.

Nevertheless, despite these promising possibilities, domestic engineering and construction firms are struggling to maintain speed. Their disqualification has created an opening work for more fruitful and capable foreign rivals. Chinese, South Korean and European firms are advancing local players and secures high price contracts all over Pakistan.

This domination is not just a matter of high machinery or deep financial resources. It reflects the commitment of operational discipline, structural learning and innovation. The main focus of this problem is low productivity, which is in a complex net of institutional weaknesses.

Poor accountability, ineffective talent management, and the absence of standard procedures lead to delay and cost increase. Many companies work on outdated models, and instead of building past experience, they resurrect the wheels with each new project. Efforts to adopt technology are rare, and when made, they often fail due to inadequate planning or training.

Perhaps the most obvious is the absence of an institutional memory. Successful international firms learn from both failure and success, and organizes insight into the framework that guide future tasks. On the contrary, Pakistani firms run the Project Two Project with a little harmony or continuity. The lessons are not seized, and errors are repeated.

Lack of long -term flexibility in local construction giants is more disturbing. In the last four decades, only a handful of firms have shown an institutional longevity. Most eliminating the most eliminated after a high-level failure, exceeding limits or void by weak internal controls. It discourages investment in the development and improvement of the system, both are essential for permanent competition.

Another critical weakness is ineffective planning and targeting. Without the ability to assess costs, timelines, or resource needs, companies cannot create reliable projects or meaningful performance indicators. The result is low performance, client dissatisfaction, and increased backwardness of local firms in large dialects.

In order to stay competitive and again on the lost ground, Pakistani construction firms have to pursue a strategic change. It begins with describing the joint set of values and measurements, which is internal at all levels. Firms should embrace performance tracking, investing in capacity, and hugging them before scaling pilot programs.

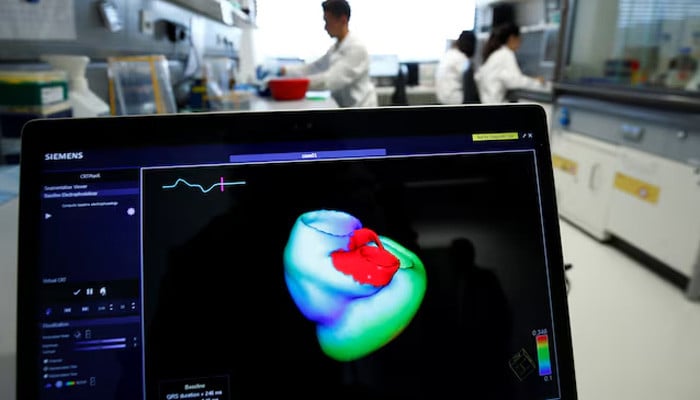

In addition, adopting technology is no longer optional. From project management software to Building Information Modeling (BIM) and AI-driving risk analysis, digital tools can dramatically improve performance and accuracy. However, effective deployment depends on a trained manpower and a distant mentality in traditional methods.

The needs of Pakistan’s expansion infrastructure should offer a great opportunity for domestic firms. But this ability will remain unrealistic as long as they shield – quickly and decisively. The industry must abandon its reaction and embrace a forward -looking, learning approach. Only then can it compete with global players and play a meaningful role in the country’s economic development.