— Photos by Benoit Florençon

#unseen #Political #Economy

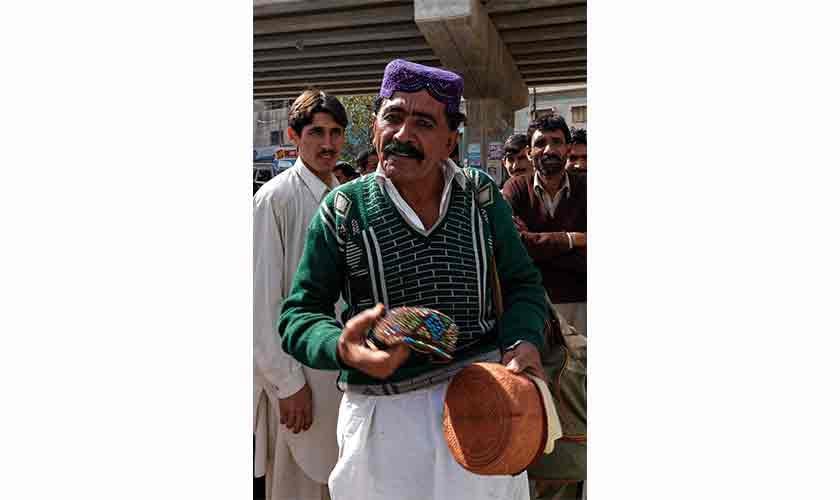

Ali Nawaz, Sindhi hat seller

Meet Ali Nawaz, an enthusiastic sixty-year-old Sindhi hat seller from Saeedabad taluk of Matiari district. Their livelihood revolves around the artistry of handmade Sindhi hats, which are known for their intricate craftsmanship. Sindhi Topi, or Topi as it is called in Sindhi and Urdu languages, is a traditional skull cap worn mainly by men. Made of fabric and decorated with elaborate embroidery, this round, flat cap dates back thousands of years, with the modern version introduced a few hundred years ago during the Kalhoro period, but coming into common use during the Talpur period.

Sporting a vibrant Sindhi cap made of bright purple thread, Ali Nawaz, with his half-lidded eyes and a broad smile, proudly asks, “Any Sindhi without a Sindhi cap to his name is a Sindhi. Won’t get away with wearing a hat, okay?” His dyed hair peeks out from under his hat. It is complemented by a thick black moustache.

Ali Nawaz has been selling Sindhi hats for many years. However, they note that Sindh Culture Day, also known as Sindhi Topi Day, celebrated on December 4, 5 and 6 every year since 2009, has significantly increased sales. This cultural celebration allows the people of Sindh to express their loyalty to the Sindhi culture and its ancient symbols. Topi Day, which was started by Hasan, a young resident of Larkana’s Balhariji district through a campaign through cell phone messages, has become a prominent event. . Along with the Sindhi ajrak, worn by both men and women, Sindhi hats are a symbol embraced by men of all ages.

On a slow day, Ali Nawaz can sell just four caps, each meticulously embroidered and stitched by the women of his village who devote about a fortnight to a piece. The circular Sindhi cap, uniquely designed with a front cutout exposing the forehead, is a source of pride for Ali Nawaz. He says he carries a hundred hats, with designs of geometric and floral patterns, often decorated with small pieces of mirror that “glow in the sunlight all day long. In the moonlight they look like stars.” are like those who dance all night,” says poet Ali Nawaz with a smile.

Ali Nawaz’s wife and children, five daughters and a son, live in the village while he moves from city to city. In Karachi, when he lives in the servants’ quarter section of Sain Amjad Hussain’s house. Ali Nawaz is his mureed or religious disciple. From 8:00 am to 8:00 pm, he roams the city offering his Sindhi hats. His routine starts the day after breakfast, with lunch at a nearby restaurant, consisting of choosing a cheap meal of “dal (dal) or sabzi (vegetables).” It does,” he smiles again.

Ali Nawaz’s journey as a Sindhi hat seller is not just a source of income but also a cultural odyssey, weaving together tradition, craftsmanship and personal connections. As he ventures across cities, his vibrant hats become not only accessories but also an embodiment of Sindhi identity and heritage.

Soraya, a cleaning cloth seller

Soraya, originally from Quetta, Balochistan, moved to Karachi several years ago with her husband and two young children. For more than two decades, she has been a familiar face near traffic signals and petrol stations, loitering in cars and buses, cleaning clothes for drivers and pedestrians.

Her story takes a poignant turn when Surya recounts the loss of her husband, a driver who suffered a stroke a few years ago. “We were never rich, but after my husband’s death, a very difficult struggle began,” she muses. Left to raise her six daughters and one son, Soraya now lives with her five children in a modest two-room house, paying a monthly rent that keeps rising.

The responsibility of running the household falls on Soraya’s daughters, two of whom are now married. They engage in daily activities, occasionally doing small sewing jobs. Meanwhile, his son follows in his footsteps, selling clothes to dry cleaners in another part of the region. The family’s situation worsened when Soraya fell from a moving bus, breaking some of her front teeth. Despite the odds, she maintains a resilient spirit, even humorously wishing that her replacement teeth were gold, not brass.

Traveling in overcrowded buses is a daily struggle for Soraya, but she has grown accustomed to the inconvenience. She finds solace in the kindness of people, especially in the places where she cleans her clothes. Workers at petrol stations, in particular, share lunch with him, exemplifying the kind of friendship that sometimes emerges in unexpected places.

Soraya earns between Rs 500 and Rs 800 a day, from cleaning clothes of different patterns, sizes and colours. He is aware of the humble origins of his merchandise, explaining that it was probably made from old T-shirts, flannel shirts and nightgowns bought from second-hand markets. A particular store is its source of supply. The price varies, depending on the quality and size of the fabric. “People use it to clean their cars or windowpanes, and dust, or clean spills,” she explains.

Seeking variety, Soraya occasionally adds safety, pins, hair combs, spools of colored threads or belts to her inventory. These items are presented with a similar entrepreneurial spirit at traffic lights, where they appeal to potential customers. Thanks to her tenacity and resourcefulness, Soraya takes on challenges as she zigzags between cars on the road that is her life.

The author is a writer, illustrator and educator. He can be contacted at husain.rumana@gmail.com.