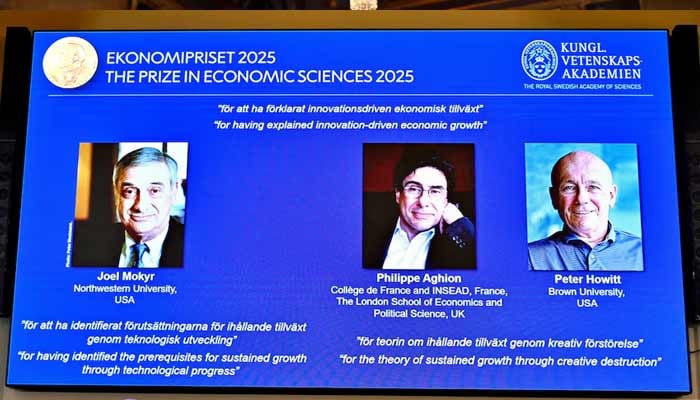

Powergrids are seen next to the NTPC (National Thermal Power Corporation) power plant in Solapur, India, March 3, 2025. — Reuters

#Indias #80bn #coal #boom #runs #water

Chandrapur: The most stringent months for the people of a hot, barren district of Western India, Solapur, began in April, where the temperature increases with the rise. At the height of the summer, residents can wait a week or more to flow from their taps.

According to local authorities and residents, only ten years ago, water was supplied every other day in Solapur, which is about 400 400 km from Mumbai.

It changed in 2017, when a 1,320 MW coal -fired power plant began to operate. Although it brought the most essential electricity to the district, it began to pull water from the same reserves relied upon by homes and businesses-which already intensifies the competition on the resources of stress.

Solapur describes the catch 22 facing India, with 17 % of the planet’s population but only 4 % of its water has access to resources. The world’s most populous country plans to spend about $ 80 billion on water hungry coal plants by 2031 to provide electricity to growing industries such as data center operations.

According to the Reuters Ministry of Electricity, the majority of these new projects have been developed for the drought of India’s most dry areas, which is not public and officials were formed to track development.

Of the 20 people interviewed by Reuters for this story, including Power Company executives, energy officials and industry analysts, the thermal expansion has potentially offered future disputes between residents of more than industry and water resources.

Of the 44 new projects named in the shortlisted ministry of future works, thirty -seven are located in areas that the government either ranks in dehydration or stress. The NTPC, who says it pulls 98.5 % of its water from the water -pressure areas, is one of the nine.

The NTPC said in response to Reuters’ questions that it “is trying to protect water with our best efforts in Solapur,” which includes the use of methods such as water treatment and reuse. He did not answer questions about possible expansion plans.

The Indian Ministry of Power has told the lawmakers in Parliament, recently in 2017, coal -fired power plants are determined by factors, including access to land and water, and the state governments are responsible for allocating water to them.

Two groundwater officials and two water researchers told Reuters that access to the land was dominant.

Rododp Majumdar, an energy and environmental professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies in Bangalore, said that India’s complex and arcan land rules have delayed many commercial and infrastructure projects for years, so the power operators will be very pressing.

“They look for areas with ease of land,” he said. The minimum resistance to the maximum land – even if the water is only available. “

Along with the Federal Power Ministry, energy and water officials in the state of Maharashtra, where Solapur are located, did not answer the questions.

Delhi tried to reduce the dependence on coal before changing the track after a quad pandem. It has invested heavily in renewable energy sources such as solar and hydro, but thirsty thermal strength will still prevail in the coming decades.

Former India’s top energy bureaucrat Ram Vinay Shahi said that access to power for the country is important in terms of strategy, whose per capita power consumption is far less than its regional rival China.

“We have the only source of energy in the country,” he said. “Between water and coal, coal is preferred.”

‘Nothing’ in Solapur?

Rajani, a resident of Solapur, plans to live around the water in the wholesale summer. In the days with supply, “I don’t pay attention to anything other than storing water, washing and such work,” said the two mother of the two, who strictly nourishes the use of her family’s water.

Federal Minister Sushilkumar Shinde, who approved the Solapur plant in 2008, when the area was already classified as “water shortage”, told Reuters that he helped the NTPC talk to the locals by discussing payments.

A member of the Opposition Congress Party, who won the elections a year after the approval of the plant, won the elections to maintain the parliamentary seat of Solapur, defending the operation on the basis of NTPC’s major investment. The 34 1.34 billion plant created thousands of jobs during its construction and now provides part -time jobs to about 2,500 locals.

“I made sure that the farmers got a good amount of money for the land acquired by the NTPC,” he said, adding that the local authorities’ mismanagement was responsible for the shortage of water.

Sachin Ombees, a Solapur Municipality official, admitted that the infrastructure of water distribution has not maintained the population increase, but he said officials were trying to resolve the issue.

Shinde said that in 2008, there was “nothing” in Solapur and that the land payments had no reason to oppose the plant.

Researcher Shripid Dharramad Kerry, who founded the Manthan Adhian Kendra, a group of environmental lawyers, said that local politicians often supported infrastructure projects to increase their popularity.

He said that no one “troubles out a lot later.”

Before the work of the Solapur plant began, there were signs of incoming problems. According to the 2020 regulatory filing, the first of its two units had to start generating electricity by mid -2016, but due to severe water shortage, it was delayed by more than 12 months.

The absence of a nearby water resource meant that the station pulled the water from a reservoir about 120 km away. Dharma Kari and two sources of plants said such distances could increase the risk of costs and water theft.

According to the latest available federal records, by May 2023, the station is effective with the minimum water in India. According to the government’s think tank tank tank Netty Iog data, it also has the lowest use of coal -fired plants capacity.

The NTPC said that its data shows that the Solapur plant has a proportion of performance according to the principles of the country.

According to the think tank of Science and Environment based in Delhi, Indian stations usually use double water from their global counterparts.

Solapur plant officials told reporters in March that the use of capacity will improve with increasing demand, which shows that water consumption may increase in the future.

Under the leadership of state -of -the -art water authorities, the next survey of water use in Solapur and writers has been reviewed by Reuters that the demand for irrigation in the district is forwarded to a third.

The Dharmais is a few miles away from the Wagmore plant and said that its development will provide more financial protection than its current comfortable work.

But he said that it is a great risk to take money to develop the land by digging the bore well: “What if there is no water?”

Authorities are struggling to attract the business to Solapur, a senior local official, Kiladip Junging, said.

“Water deficiency neutralized all other factors,” he said.

Water thirsty

Since 2014, India has lost 60.3 billion units of coal power across the country – which is equivalent to 19 days of coal power supply at the June 2025 level – because water shortage plants are forced to suspend breeding, according to federal data.

Of these facilities that are struggling with shortage, 2,920mW is Chandrapur Super Thermal Power Station, which is India’s largest.

According to Nety Iog data, about 500 500 km northeast of Solapur, but in the water pressure area, the plant closes its several units at a time for months when the monsoon raines less than normal.

Despite the challenges, the plant is considering adding a new capacity to 800 MW, according to the Ministry of Power, which has been viewed by Reuters and has half a dozen sources in Mahaganko running the station.

The document shows that the plant has not identified water sources for extension, though it has already obtained its coal.

In public ownership, Mahaganko did not answer Reuters’ questions.

The water thirst for the plant has led to tension with residents of the nearby Chandra city. Locals protested at the station during the 2017 drought, which allowed officials like local lawmakers Sadhir Mangantur to order him to be diverted in his homes.

Mongantwar, however, says that he supports the expansion of the plant, which he hopes to retire older units with water.

Sources in the company said that the station, citing the federal government’s instructions, has already delayed the plan to reject two pollution and water -powered power units, citing the federal government’s instructions.

According to Reuters, the Indian government asked power companies not to retire old thermal plants by the end of the decade due to increased demand after pandemic disease.

Chandpur resident Anjali, who goes under the same name, said he had resigned from a tap -tapped by a station near one of his gates for drinking water.

“We are poor, we do with what we can get,” he said.