#fame #glory #Political #Economy

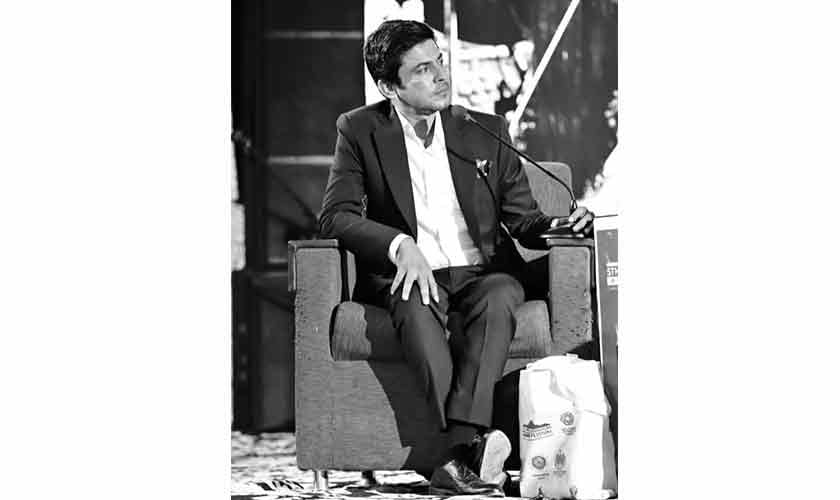

He shines the camera, crowded murmuses and he stands there – the fastest, between the two Bollywood megasters, is under the shining light of Dubai. At first glance, this is just another glamorous event. But look closely. The confidence in his position and the pride in his eyes tell another story. This is not just another celebrity snapshot. It has been the lap of victory for twenty years. The story started not on the red carpets but in the sunny streets of Sindh, where a young boy dared to dream bigger than his surroundings.

In a small village in Sindh, where most of the children’s ambitions rarely move beyond their immediate horizon, the young man was different. When his colleagues played cricket in the dusty streets, he felt himself matched through photos shining on the family’s small television set. “I just didn’t see those shows,” he remembers running one hand with his hair. “I studied them. Camera angle, lighting, actors presented their lines – it attracted me.”

His father, who is a school teacher with modest sources, saw his son’s extraordinary interest. “Most parents in our village wanted their children to be a doctor or engineer,” Mazhar remembers with a dirt. “My father? He just wanted to be happy. When I told him that I wanted to work in television, he didn’t laugh. He just asked, ‘How can I help?’

This simple question became the basis of everything that happened after that. With the encouragement of his father, the mazar started his life around him using a borrowing camera. His first “production” was humble – interviews, etc.

Mazhar’s journey took a turning point when he enrolled at Shah Abdul Latif University. While studying Sociology, he discovered an unexpected benefit. He says, “Understanding human behavior is the most powerful tool that can be a storyteller.” “My degree taught me why people work in the way they move them. What do they move. What they have to change. They were not just educational lessons – they became the backbone of my skills.”

“There were many nights when I thought about leaving,” he says. “The goods were basic, the budget did not exist. But then I will remember that the little boy from the village was stuck on the TV and I will keep going.”

Its progress came with a show in the local channel. “It was rough, it was a fact, and most importantly, he felt something to people.” The film drew the attention of the local media, which led to the first professional opportunities in the TN of a well -known Sindhi television network.

The television studio was pleasant and scary. “I started as the host of the talk show, but I wanted to do everything,” says Mazar, his eyes are highlighting memories. “I traveled the cameramen to teach me about the lenses, requested the editors to explain their technique. Some probably felt annoying. I didn’t care. I needed to learn.”

His perseverance ended. Soon, Mazhar was instructing music videos that stood for his cinema standards. He says, “Most local production followed the same formula.” I wanted to break the mold. If we were shooting for a song of love, I would insist on the places that told a story. If it was a folk tune, I would research traditional costumes and customs to ensure that it is authentic. “

He confessed, “There were many nights when I thought about leaving.” “The goods were basic, the budget did not exist. But then I will remember that the little boy from the village was stuck on the TV, and I will keep going.”

This focus on the details was not focused. His work began to draw attention to Sindh, which resulted in the partnership with artists from all over Pakistan. But Mazhar wanted more. He says, “I kept thinking about the international content I see.” “I knew that Pakistani stories could resonate globally. They just need the right offer.”

The decision to move to Dubai was equally frightening and pleasant. “I brought two suit cases and a portfolio of my work,” Mazhar remembered. “The first month was wandering. I went to countless meetings, showing my train to anyone who sees it. There were polite nodes and vague promises, but no real opportunities.”

Then progressed – a small commercial for a local brand. “The budget was small, but creative freedom was very high,” he says. Mazhar put everything in the project, and treated it like a Hollywood production. A place that looked more expensive than that, catching the eyes of major advertising agencies.

Soon, Mazhar found himself in seats with Bollywood stars and international models. He says, “For the first time when I directed a famous actor, my hands were shaking.” “But then I remembered – I earned it. My Sindhi roots, my struggle, all these years to work with limited resources – they prepared me for that moment.”

Today, the work of the manifestation is spread in the continents. From advertising to Hollywood projects in Dubai, it has become a bridge between Eastern and Western media. They say, “What I bring to the table is a context.” “I understand the two worlds – the traditions of telling the story of South Asia and the productive values of the world media.”

Success has not weakened its roots. Fazils regularly return to Sindh, young people do workshops for film banners. He insisted that “talent is universal,” is not an opportunity. If I can help open the door for a child from the background like myself, this is more meaningful than any award. “

His latest project is about youth. This is a podcast series that highlights the unruly stories of youth models from rural Pakistan. He said fondly, “This world needs to be heard.” “Poverty is not pornographic, but the real stories of flexibility, innovation and hope. It is the power of the media. It can change a frame at a time.”

When we embrace our conversation, the fun leans, its voice falls in a secret tone. They say, “People ask if I have ‘made it?’ “But this is the wrong question. The real question is, what do I want to tell the story? “

With a feature film and digital platform projects to show South Asian capabilities in work, no signs of slowdown are shown. “Twenty years ago, a village boy dreamed of standing at this stage,” he reflects. “Today, I’m thinking about making a platform for others.”

His phone resonates – another call from Dubai. When he is preparing for his next meeting, the mood offers a final idea: “They say that you can take the boy out of Sindh, but you cannot take Sindh out of the boy. Well, you should not try to take Sindh out of the boy. This is the place where magic comes from.”

The camera shines again. This time, it is not just occupying the international filmmaker Mazhar Setter. It is also catching the little boy from the village who has not forgotten where he came from.

The author is an independent journalist. They tweeted @rehmattunio