#forgotten #voice #Political #Economy

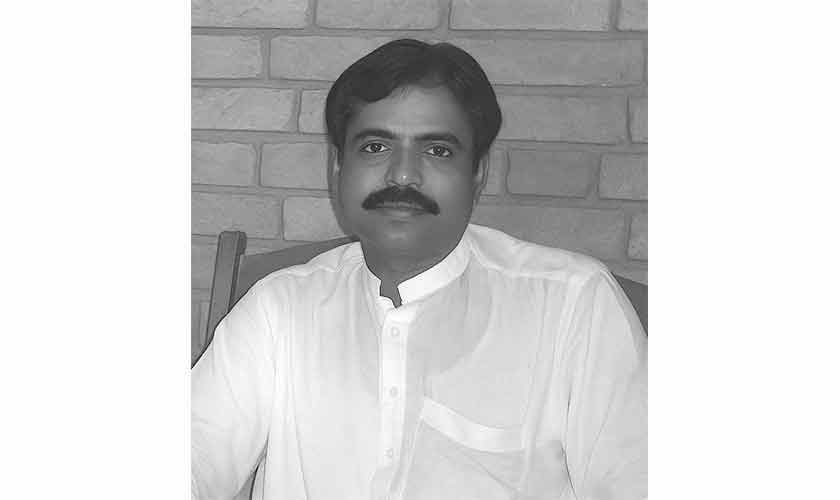

n Pakistan’s minority politics scattered archives are the forgotten story of a man who devoted his life to one of the smallest and most backward communities in the country: Buddhist Buddhist in Sindh. Achawar Shah Naik, who was born in Mehrabpur in Nowshero Feroz district in 1967, dedicated decades to public service, yet his name is absent from the national memorandum.

The son of Naik Kimo, who is officially known as “non -Muslim, Buddhism”, was unusual for anyone belonging to a modest rural background. He received a postgraduate degree in economics, international relations and sociology from Shah Abdul Patif University, Khairpur. He also achieved legal training and joint educational success with low level activity. By the beginning of the 1980s, he had entered the passages of federal politics. In 1982, the Minister of State for Minorities Peter John Sahutra welcomed his appointment to the Federal Advisory Council for minorities, in which his role was described as important to tackling the problems of lower representative groups. The importance of Naik was confirmed in 1992, when he was re -added to the Council and was given the task of compiling “National Importance” proposals. But its original impact is beyond the government forums, where it served as a reliable brave between the state and the neglected communities.

During the devastating flood of 1992, the confidence became clear, when Parliamentarian Bayram Da Aory recommended Naik monitoring aid distribution in Buddhism, Parsis, Sikhs, Baha’is and Kalash families. Local officials were instructed to cooperate with it. Records showed another aspect: Communities were out of relief schemes, leaders forced to beg for identification. He wrote in a petition that “it is painful to explain that the Buddhist community has been completely ignored.” His words were quick and calm frustration, which exposed the inequality of relief goods.

Beyond the emergency, Naik’s advocacy maps the weaknesses of everyday life. He requested for residential plots and ground certificates, which were suppressed to supply electricity to Buddhist palaces, requested teachers’ appointments and scholarships and requested for the protection of cemeteries and community centers. These appeals were not for privileges, but for the basic guarantee of citizenship.

The ancient Buddhist heritage of Sindh was placed against the background, this struggle looks particularly violent. Once the monasteries and stopping houses that came through pilgrims like Zawan Zhang, the presence of Buddhism of Sindh by the end of the 20th century decreased to small, poor clusters. Their applications for the walls of electricity or cemetery are in stark contrast to the great ruins that testify to the historical site of Buddhism in the region.

Naik’s career also represented the minority of Pakistan’s disturbing history. Since independence, the state has a dispute between different systems. Under General Zia -ul -Haq in 1985, minorities were given “separate election”, only by voting for co -religious candidates, the mainstream was cut off from politics. In 2002, the system was transferred to common constituencies with specific seats, but seats are allocated by party leaders by lists, which do not directly choose by minority voters. This meaning of micro -minorities like Buddhist, this means nearly hidden. Although Christians or Hindus could sometimes keep their representatives, Buddhists lacked numbers and riots to secure the seat. People like Naik can sit in consulting councils or relief committees, but their community remains unprecedented in Parliament.

Remembering Naik is a historical justice. He showed that the Buddhists of Sindh were not passive in the past but were active citizens who wanted education, representation and dignity. His life identified a truth that still resonates: without accountability, consulting councils and safe seats are not enough. Real representation requires sound. Naik just tried to tell her life.

As Federal Minister Raja Tri -Rai noted in 2009, as many small groups as Buddhism and Kalash could never get a fair representation under this system. Naik’s life – spreading council appointments, relief efforts and community organizing – influenced the contradiction: it was acknowledged by the state, yet unable to secure system change.

In the later years, disappointed with domestic neglect, he saw abroad. At the Buddhist Festival of Light in 2000, he wrote to foreign ambassadors who wanted to assist in the fight against poverty and illiteracy in Sindh’s Buddhists. “I want to keep the basic stone of the mission of life,” he announced, appealing for international solidarity after eliminating local routes. His tone was neither polite nor solid, which indicated both frustration and flexibility.

Nike’s efforts rarely made headlines. He was known in the bureaucratic circles, he was respected by a handful of parliamentarians, but was hidden to the wider people. When he died in 2016, he died in national newspapers. No tribute was paid, no memorial was made. What is left is the scattered letters, the official memo and the memories of a person who refused to quietly take his community.

Today, outside Sindh, a few remembrance of Naik remembers. Its name does not appear in Pakistan’s political dates, nor does the Buddhist heritage, which focuses more on ruins than living communities. Nevertheless, his life opens the window in the unprecedented struggle of religious minorities. His story is not a personal victory, but of a permanent dilemma: What does representation mean when communities cannot choose their leaders? What is the meaning of equality when the smallest minorities remain unnoticed, even in the systems designed to add them?

Remembering Naik is a historical justice. He showed that the Buddhists of Sindh were not passive in the past but were active citizens who wanted education, representation and dignity. His life indicates a truth that still resonates: without accountability, consulting councils and safe seats are not enough. Real representation requires sound. Naik just tried to tell her life.

His advocacy, which has been neglected in his time, talks powerful today among new debates about religious freedom, minority rights and cultural protection. Naik’s story reminds us that leadership is not always about mutuality or power, but rather about refusing to forget anyone’s people.

Author is a visiting senior research fellow in the University of Texas, Texas, Humanology.