#Turning #waste #wealth #Political #Economy

East is not just about what we throw. This is about what we choose to value as a society. Plastic bottles, food packaging, and piles of flowing cans on the streets of Islamabad are not just one eyes. They are a mirror that reflects the collective apathy towards our habits, the differences of governance and stability. For a long time, Pakistan has gripped with a linear approach to production, use and waste, without fully understanding the environmental, health and economic costs of this cycle. Nevertheless, since Islamabad has taken sarcastic steps to modernize its garbage collecting system, introduce fines on garbage, and experiment with multi -bean models, we stand at a turning point. The question is: Will we take advantage of the fact that we manage the garbage, or we will solve for cosmetic changes that work very little to convert this system to this system?

The recent announcement of the Capital Development Authority for the restoration of the city’s waste framework is certainly a promising move. Dividing the capital into the operational zone, launching a new bin system for homes and commercial centers, and bringing financially strong international quality services providers all indicate a serious one, which has long -term. The important thing is that the decision to introduce fines for garbage, an implementation move that, if applied permanently, can renew public behavior in a deep way. Pakistan has often struggled to translate policies in practice, but emphasizing transparency in the bidding process, real -time monitoring through the central control room, and material recovery facilities show that Islamabad is eventually closer to world standards.

Nevertheless, the real challenge is not only in institutional reforms but also to change the culture of waste management. At present, Pakistan produces more than 48 million tonnes of solid waste annually, and plastic waste is one of the most threatening threats. Cities like Islamabad can appear green compared to Karachi or Lahore, but the hidden problem is due to separation, recycling infrastructure and lack of awareness among the citizens. Even the most sophisticated systems have to be damaged if the residents are not sensitive to their proper use. This is a place where the new Bin Model, if combined with educational campaigns, can give rise to the beginning of a change of behavior.

Particularly plastic waste deserves immediate attention. In some provinces, the only use of plastics has been contradictory, despite the ban on plastics, and alternatives to ordinary citizens are either very expensive or inaccessible. Pass through the markets of Islamabad, and for most shopkeepers, plastic bags have been made predetermined. The policy differences here are clear here: We cannot illegally make plastics illegally without investing in cheap biodegradable alternatives and encourages businesses to innovate in packaging. If the government wants to succeed, it will have to create a capable environment where alternatives to plastic are not common but normal. This requires mutual cooperation between policy makers, private businesses and research institutes to develop and measure sustainable powers.

From a policy analyst’s point of view, the most interesting aspect of Islamabad’s new garbage strategy is to include material recovery facilities and green waste separation. These are the first steps towards transfer from linear to circular economy. Instead of viewing the waste as the closing product, we need to see it as a resource stream: plastic that can be recycled into construction material. Organic waste that can be converted into apex or bio -energy. And glass or metal that can re -enter the industrial supply chain. Countries like Sweden and Japan have shown how to create jobs simultaneously in waste energy measures and circular methods, reduce dependence on landfill, and contribute to energy safety. Pakistan should not refrain from learning from these models, instead of wholesale copying them, adapt to local facts.

Fine for dirt, while necessary, should also be paired with privileges. Citizens can be resolved without offering a solution. For example, the award -based recycling program, where citizens get discounts on utility bills or irreparable credit for returning recycled items, has proved to be effective in cities in Europe and East Asia. Islamabad can pilot such schemes through digital apps or community centers, which can take advantage of Pakistan’s growing digital infrastructure to encourage participation. This will not only reduce the burden on the waste collection system but also promote the sense of ownership among the residents.

Another important dimension that cannot afford to ignore Pakistan is a link between garbage management and climate flexibility. Floods, smogs, and urban heat islands all grow in poor ways to waste waste. Plastic -filled drains contribute directly to the floods, while uncontrollable waste increases air pollution and public health crises. If Islamabad’s reforms are meaningful, they should be embedded under a broader climate strategy that recognizes waste not only as environmental issues but also as a threat to disasters. Connecting garbage management with the risk of destruction reduction plans, especially in the weak urban rural transfer zone, is essential to create flexibility.

That is important to include young people in this process. Pakistan has the youngest population in the world. Their energy, innovation and digital salvation can be used to advance new ways. From developing biodegradable packaging to university -led awareness campaigns and neighboring recycling drives, young people can be at the forefront of changing garbage management in people -driven movement. Islamabad should empower its youth to design, implement and monitor community -based solutions.

But as we look at the solutions, we must also recognize the basic political economy of waste. In Pakistan, garbage management agreements are often affected by incompetence, corruption and lack of continuity. A system that relies heavily on outsource companies if the accountability methods are weak, with the risks of falling risks. Transparency in purchase is a good starting point, but it should be competed with the construction of long -term institutional capacity. Strengthening municipal organizations, ensuring harmony between local and federal agencies, and creating a platform for citizens’ opinion can help protect against systematic failures.

Ultimately, the change of Islamabad’s garbage management system cannot be reduced to just triangles, trucks or fines. This requires restoration of our relationship with the garbage itself. Do we continue to behave as an indispensable side product to hide it in landfills or do we accept it as an opportunity to innovate, recycle and re -create?

The path forward is clear: Combine institutional reforms with the engagement of citizens. The enforcement of the pair with concessions; And invest in sustainable alternatives while promoting innovation. Waste, however, is not just a municipal issue. This is a social. By re -considering waste as a resource, aligning policies with climate flexibility, and empowering young people as transformations, we can move beyond cosmetic reforms towards ensuring clean, more sustainable and future cities.

If we succeed, it can be a model how developing countries can turn waste into opportunity. But if we fail, we are at risk of drowning in plastic and carelessness piles that are around us today.

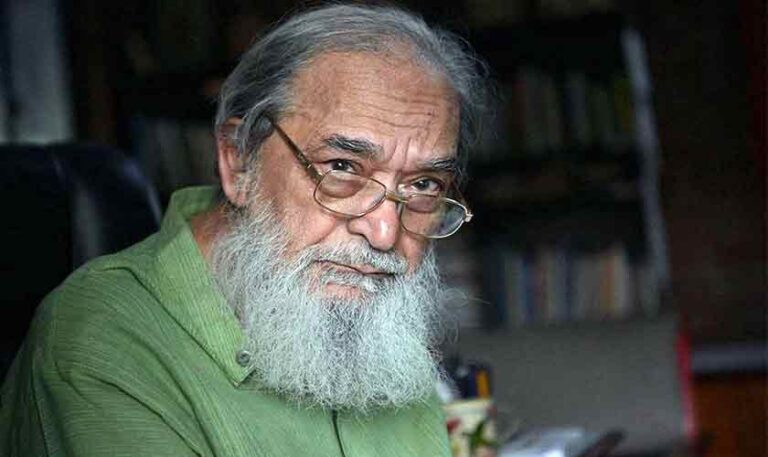

Author is a policy analyst and researcher who holds a master’s degree in public policy from Kings College London