#Passing #baton #Chinese #conductors #seek #global #fame

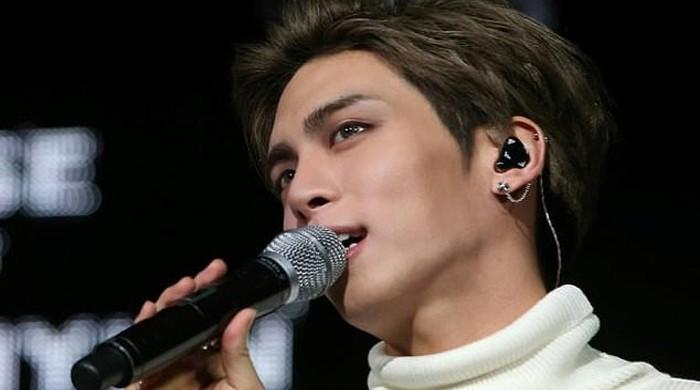

BEIJING: Jing Huan nervously twirls her conductor’s baton as the brass and string sections of China’s Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra tune their instruments.

At 36, Jing is part of a new generation of foreign-trained conductors, as China hopes to gain recognition in the field after gaining global fame for its soloists, including piano and string virtuosos.

After long relying on Western conductors, a growing number of symphony orchestras across the country are now turning to a new generation of Chinese music directors.

Zheng studied at the University of Cincinnati and served as conducting assistant of the Symphony Orchestra there before joining the Guangzhou Orchestra in southern China.

Last year his orchestra performed on a prestigious stage in Beijing as part of the “Musical Marathon”, playing nine consecutive duets to mark the 20th anniversary of the Beijing Music Festival.

“In China, at the Central Conservatory of Music, we focus on technique,” he told AFP. “So technically, we’re very strong… but as a young conductor you don’t have many opportunities to do a real orchestra right away in China, whereas in America, getting a lot of experience early on. It’s easy,” he said.

According to prominent music critic Zhou Yao, China now has about 80 symphony orchestras — supported by local governments that view Western music as prestigious — up from about 30 just eight years ago.

“But the shortage of conductors persists: most orchestras are led by Chinese, but sometimes one conductor can be in charge of three orchestras!” Zhou said, pointing to the lack of “small musical groups” that would allow young conductors to gain experience, as in the West.

‘Chinese-style Beethoven’

But China has come a long way, said Long Yu, 54, artistic director of the Shanghai and Guangzhou Symphony Orchestras and founder of the Beijing Music Festival.

“I grew up in Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution,” a period of political turmoil from 1966-1976 during which Western music was banned, the teacher told AFP.

Long secretly learned piano from his grandfather, a famous musician, and became one of the first Chinese musicians to study abroad in the 1980s when the Communist regime began to open up to the rest of the world.

He trained in Berlin before returning to China in the early 1990s, where management was difficult.

“It’s a very special job,” he said. “You have to give a message to the musicians themselves about the interpretation of the music, so it’s It’s quite difficult.”

When he hears about the “Chinese style” of playing classical music, Long’s crushes on him.

“There is no such thing as Chinese-style Beethoven!”, he said.

Jian Wang, an American-trained violinist, said performing in China still has its own challenges — and rewards.

“Playing in China is very exciting and challenging at the same time (because) part of the audience is hearing his pieces for the first time,” he said.

In addition, most musicians in Chinese orchestras were trained as soloists.

Ten years ago, French conductor Emmanuel Calef faced this problem when he took the podium with the Guiyang Symphony Orchestra, a private institution in the remote southwestern province of Guizhou.

Musicians of the 20s were “technically ready, but not culturally ready, and they weren’t trained to participate in a collective effort,” he told AFP.

He also remembers the “culture shock” when he realized that neon signs would light up to tell the audience when to clap.

The French conductor smiled, and while the wealthy businessmen who financed the orchestra were willing to rent a prestigious Steinway piano or an expensive Amati violin, they were reluctant to buy a standard score.

“It Takes Time”

Ten years later, classical music is no longer seen as an “imported product” in China, although repertoire is often limited to “very big” composers such as Beethoven, Bach and Brahms, Califf said.

For more modern composers, “some (Chinese) composers have the same reaction that their Western counterparts had when they discovered the score in the late 19th or early 20th century,” he said.

Long agreed, but said the stock is growing slowly as the public becomes more familiar with it. “It’s a culture that’s still exotic today, and there’s still a lot of work to be done.”

The real difficulty for him is that few Chinese conductors have won acclaim abroad.

Notable exceptions include the Chinese pioneer Tang Mohai, who conducted the Berlin Philharmonic during the 1983-1984 season, then went on to a successful career in the US, Portugal, Australia and Finland.

There are other examples such as China’s Zhang Xian, who in 2009 became the first female music director of a symphony orchestra in Italy in Milan.

“Conductors from China, Japan, Korea and Singapore have incredible talent, but I don’t think Asian conductors have been fully accepted in the West yet. It takes time,” sighs Long.