#Problematic #obedience #Political #Economy

Hannah Arendt’s insights into the psychology of obedience have found deep resonance—and some challenge—in the work of social psychologists who have explored how ordinary people engage in loss. The classic experiments of Stanley Milgram and Philip Zimbardo are particularly revealing. Milgram’s Obedience to Authority study, conducted in the early 1960s, was designed to test how far an authority figure would go when directed to harm another person. Participants were assigned the role of “teachers” when the voltage was increased each time the voltage was increased. The learner’s cries of pain were pre-recorded, but the subjects believed them to be real. Despite hesitation, sixty-five percent of the participants reached the maximum voltage, only because the experimenter, wearing a lab coat, told them they should continue.

The standard interpretation of Milgram’s findings is that normal individuals may commit harmful acts when obedience displaces moral agency. Authority can numb the conscience. Moral autonomy dissolves into procedural compliance. Milgram’s work was often presented as an empirical counterpart to Arendt’s “restraint of evil,” showing how decency comes not from hatred but from the comfort of obedience. Later researchers such as Alex Aslam and Stephen Reicher refined this theory, arguing that people don’t turn a blind eye—they obey when they identify with authority or believe the cause is legitimate. In this sense, obedience is not passive surrender but active alignment. We follow because we want to be followed.

Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment dramatized similar dynamics a decade later. College students were assigned as guards at a mock prison, quickly adopting abusive, humiliating behavior with the cast as fellow inmates. The experiment, which was intended to last two weeks, had to be terminated after six days. The lesson was not simply that power corrupts, but that role structures, group identities, and cohesion can make oppression feel normal. Zimbardo later drew clear parallels between his findings and modern political tyranny, noting how the demand for incivility and loyalty can reproduce the mentality of guard leadership in populist movements and state practices.

Even earlier, social theorist Eric Fomm diagnosed the deep needs that make obedience attractive. He wrote that modern people often run away from freedom. The anxiety of choice, uncertainty, and moral ambiguity lead many people to surrender autonomy in exchange for security and certainty. Obedience is thus motivated not only by fear but also by a longing to be relieved of responsibility. Together, these thinkers show that obedience is not simply a failure to resist—it is a psychologically appealing option when the world feels unstable, fearful, or morally confused.

If obedience is strategic rather than accidental, then regimes that thrive on obedience are not anomalies—they are deliberate constructs. In contemporary politics, Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu offer two stark examples. Trump’s continued hold over American politics, even in the midst of indictment and ethics scandal, depends on a network of obedience that extends from his political base to institutions reluctant to stop him. For its proponents, loyalty itself has become a moral good. The slogan once again serves America as a declaration of faith rather than a policy proposal.

Within Congress and the bureaucracy, many officials have relegated their actions to avoid derailing Trump’s movement, while followers rationalize the complication as a duty. They see themselves not as abandoning conscience but as serving a noble cause. Trump’s persona, demanding unconditional allegiance, turns obedience into itself. Every norm violated, every lie defended, becomes another test of faith. Over time, obedience becomes unusual. It becomes reflexive. To question is to disagree. To disagree is to betray.

Netanyahu’s Israel presents a similar but differently coded pattern. His long rule has woven national identity, existential threat and political obedience into a single fabric. Whether the Israeli public is asked to equate loyalty with security—from external enemies or domestic dissent. Critics are portrayed as undermining the survival of the nation. His regime’s judicial reforms exemplify this logic: by concentrating power and weakening checks, the executive renders not only virtuous but structurally necessary obedience.

The climate of perpetual emergency allows the demand for obedience to be masqueraded as patriotism. In both Israel and America, obedience becomes a rare political currency: it defines who is and who is not.

Yet the habit of obedience runs deeper than in contemporary democracies. In much of the post-colonial world, obedience was institutionalized long before modern popularization. The colonial administration trained its subjects to equate civilization and stability. When independence came, the bureaucratic machinery of command often remained intact, simply transferred to new rulers. In Egypt, for example, the reassertion of military power after the Arab Spring reinstated obedience as a political common sense. Citizens learned that dissent invites punishment, while harmony ensures safety. Disobedience to hierarchical cultural memory appears chaotic and irresponsible.

In Pakistan, obedience has long been woven into the fabric of civil and military institutions. The military’s periodic intervention in politics, its self-presentation as the ultimate guardian of order, and a bureaucratic ethos that commits most to the accommodation of citizens awaiting “the above orders”. Even in civilian life, obedience becomes synonymous with respect. Patronage networks of political parties punish compliance and dissent.

Brazil and much of Latin America exemplify another legacy. After decades of military rule, obedience was re-designated as a civic virtue. The populist rhetoric of leaders like Jair Bolsonaro taps into this heritage. For millions whose daily lives are uncertain, obedience manifests itself in practice: a means of avoiding violence, corruption, and instability. In poor areas, where institutions are weak, obedience feels like the only viable currency.

The persistence of obedience in such diverse contexts suggests that it fulfills genuine psychological needs. It provides cognitive relief by outsourcing the decision to the authority. It offers moral hygiene by eliminating guilt (“I was just following the rules”); It socializes the individual by aligning it with the collective identity. It reduces risk by protecting someone from punishment. And it reinforces itself with a self-aggrandizing interior. These mechanisms transform obedience from an action into a mindset. Arendt’s warning thus reemerges with new urgency: in modern societies, obedience has become the default, not the exception, moral currency.

If obedience is a trap, how can it be resisted? Arendt offered no simple formula, but she pointed to an ethics of freedom. To think, he said, is to “think without restraints”—to walk without the handrails of authority or tradition. In a world where moral compasses are unreliable, each individual must cultivate an inner dialogue, a private tribunal of conscience. It is neither comfortable nor safe. It creates hesitation, isolation, and doubt, which is why many people prefer assurances of obedience. But moral maturity demands precisely this discomfort: the courage to stop and think when everyone else is marching.

Resistance, then, begins with small actions—a refusal to repeat an easy lie, a decision to question an unjust order, a willingness to protect those targeted by conformity. These cues train the moral muscles that seek to atrophy authoritarian systems. Institutions must also be designed to combat obedience: independent courts, free media, strong civil societies and protections for dissidents all create space for judgment. Cultural education must respect disobedience where it serves justice and teach citizens to value dissent as a civic virtue rather than a threat.

Arendt’s final warning feels unusually contemporary. Obedience has ceased to appear as offering. Now it passes for excellence, patriotism and discipline. In the United States, the faithful continuity of the Trump era has turned dissent into treason. In Israel, the language of national survival fuses with the demand for silence. In much of the world, obedience persists as a legacy of empire and survival strategy.

The challenge of our time is not only to stop powerful leaders but also to awaken the citizens who make their power possible. Democracy does not die when leaders disobey the law. It dies when people forget to disobey authority. Reclaiming this forgotten art—thinking, deciding, denying—is the only antidote to the foolproof strategy of obedience.

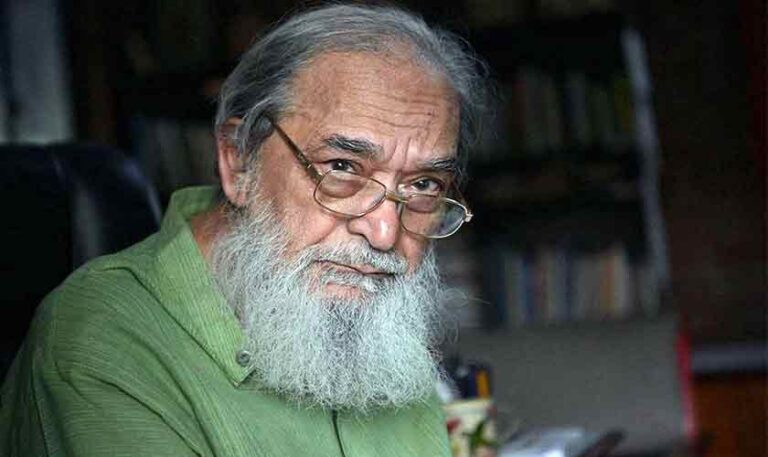

The author is a professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Beacon House National University, Lahore.