#Scars #fade #Political #Economy

The first time I saw Amy Shuro in Khatta, she was sitting in a wheelchair under a makeshift shelter, working on an artwork. The colors of her embroidery stood out against the dullness of her surroundings and sparkled in the afternoon sun. At first, she looked like any other woman sewing to earn money. But Aami’s story is written on her body in the scars that run across her neck, back and arms. They are a reminder of such brutality that she can no longer walk.

Aami was married to a much older man when she was only 15 years old. By the time she was 27, she had six children. Her youngest child was nine months old and nursing when her life fell apart.

One afternoon, while she was cooking, her husband immediately called her to help her with the work. Said to leave. He asked her to wait till the dinner was ready. This simple answer caused terrible pain.

“He suddenly hit me in the neck and hit me back with an axe. I passed out as I bled. He ran away screaming, ‘Blood, blood.’ My baby was left alone in the crib and cried,” she recalls.

His brother rushed to him, but it took him an hour to reach the nearest hospital. The damage to his spine was irreversible by the time he received medical attention. The delay was not accidental. “They said it was a domestic violence case and therefore not urgent.”

For two years, Amy lay flat on a wooden wagon. She could not move and had no dignity and no wheelchair. “I felt like I was dead, but I was still alive,” he added. Finally, he got a racquet wheelchair. After that, with the support of Sindh Rural Support Organization, he got a great movie.

The scars are on his person. Aami says, “Even after all these years, I still feel pain all over my body. A person’s hand, especially if it’s your husband, is more than just a cut. It heals but never leaves the heart.”

Forgiveness under stricture

Eventually, the police took Ami’s spouse into custody. During the trial, Ami, who was taken to court in a wheelchair, did the unthinkable. He forgave her.

“I asked the court to let him go.” “I don’t know why, but I had the heart of a wife and mother of six.”

Judges and lawyers said they were “kind.” Some women’s rights activists argue that forgiveness is not always a free choice in such situations. Marvi Owen, a gender activist, says, “Women have to fight back against their abusers because of societal pressures.” “They are told to put the children first, not their own safety.” Forgiveness under strictness is not justice. This is survival.

Amy’s decision had consequences. After getting out, her husband tried to attack her again, this time hitting her sister and breaking her arm. He ended up in jail.

A life rebuilt in pieces

Amy never lived with her husband again. She is raising her six children on her own. SRSO runs a program to help women become more independent. In 2017, he received a grant of Rs 15,000 to start a business. He used the money to start a work business.

Its application is beautiful, strong, detailed and patient. Each piece is a bit of survival sewn into the fabric. “Work became my dignity. I feed my children with this craft. Even if I can’t stand, I can sew,” she says.

Ami had built a mud house with her own money. She still lives there. It’s a fragile structure, but it’s his. She says she no longer lives in fear, but the trauma is still there. “Sometimes, when I look at my children, I feel the same pain,” she admits.

A Hidden Epidemic

Ami’s story is one of many in rural Sindh, where gender-based violence (GBV) persists, often hidden behind traditional silence. Incidents similar to his ordeal are not often reported. This practice has been attributed to lack of awareness, social stigma and the perceived futility of seeking justice.

The Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18 found that 28 percent of women aged 15-49 had experienced physical assault. Activists say the actual figure is higher, especially in rural areas. Recent statistics reveal a dire situation: in 2024, Pakistan documented 32,617 incidents of gender-based violence. These included around 5,300 rapes, 2,200 cases of domestic violence and 547 ‘honour’ killings. Conviction rates are unusual: 0.5 percent for rape and honor killings, and 1.3 percent for domestic violence.

Over 1,700 incidents of gender-based violence were reported in Sindh last year. There was no punishment. The data not only indicates under-reporting but also a systemic failure at every level of the legal system.

Women’s rights organizations emphasize that economic dependence traps women in abusive relationships. Research shows that rural women’s participation in the formal labor force is less than 30 percent. A significant part of is free.

The Sindh Commission on the Status of Women recognizes the discrepancy between the law and its implementation. According to Additional Deputy Commissioner, Thatta, Ghulam Dastgir Shaikh, implementation of the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act, 2013, has been inadequate, especially in rural areas. “Survivors are forced to return to abhorrent environments in the absence of legal aid, medical aid and shelter.”

Research gaps

Recent feminist scholarship points to the failings of Pakistan’s GBV response. A 2023 study in the Asian Journal of Women’s Studies noted that rural survivors often face “secondary victimization.” Another UN Women report highlighted that less than 10% of GBV cases in Pakistan are the result of legal action.

These findings call for a re-examination of official statistics. While 32,617 cases of GBV were “recorded” in 2024, activists argue that the figures barely scratch the surface. The vast majority of rural affairs are hidden, erased by silence, stigmatization and indifference.

Survival as resistance

Amy sees life as a fight. Every stitch she makes in a dress is a way for her to force herself to be. “I only think of living with dignity,” she murmurs, her hands resting on the fabric.

She still has her scars but Ami says she lives in her appliqué, in a mud house she built and raised six children on her own.

Pakistan should focus on cases like these to eradicate the scourge of violence against women. Laws on paper mean nothing if they are not enforced. Survivors like Amy don’t have to choose between forgiving someone under pressure or staying silent to survive. Without it, the wounds of violence will not heal.

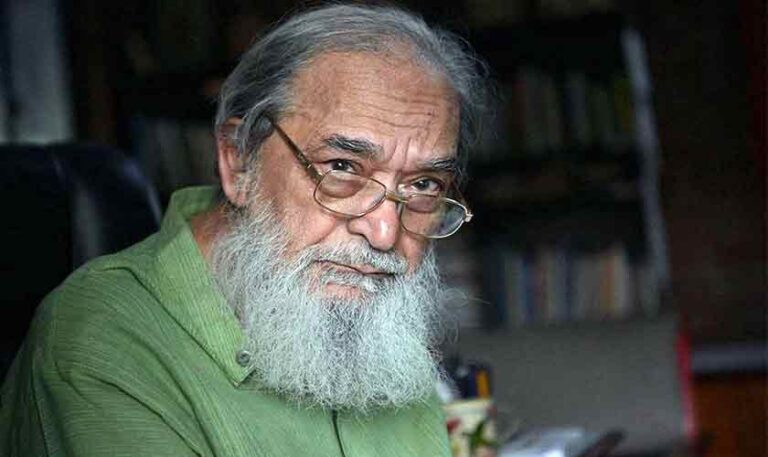

The author is a researcher and writer working as a development practitioner in Hyderabad, Sindh. He holds a master’s degree in English literature. He can be reached at quaxigm@gmail.com