#Pink #green #Indonesias #season #reckoning #Political #Economy

It began with a seemingly disagreement over a pork. In Jakarta, lawmakers, who are already widespread distrust, approved a new monthly housing allowance – which is ten times higher in the minimum wage in the capital. In a country where millions of workers only rotate several jobs to cover rent, rice and transportation, it was revealed like a slap on the face.

Indonesia is not a stranger to strengthen itself in inequality or elite. A 21 -year -old delivery driver caused by anger was the death of horizontal Karniawan, when an armored police vehicle was plowing into a crowd of protesters. In the green vest of a fiancé worker, opium was made from anonymity to the martyrdom overnight. His destiny has come to make the gulf between the ruler who involves himself and the citizens who take the risk of their lives in uncertainty – and, now, in protest. This justification – the golden allowance of a few people, the green uniform of many – the explosion of something big. Suddenly, what could happen has been another cycle of corruption in Indonesia’s biggest political unrest in the years.

For many Indonesian residents, the riot has given rise to the uncomfortable memories of 1998, when the students’ protests abolished the new three -decade -long order of Swarato. Then, as now, the students were on the fronts, the voices of women became rapidly prominent, and the anger was intensified due to the economic crisis. There was many years of corruption and corruption before the fall of Soharto, which was suffering from police and military reactions that had left blood on Jakarta’s streets.

Today, the context is different. Indonesia is democracy, not dictatorship. President Prabo Sabnto, Soharto’s mother -in -law, law, insists that he is committed to reform and stability. Nevertheless, under a state car, a young delivery worker’s body symbolizes the darkest days of state violence. Demonstrators know their history, and many deliberately say in 1998 slogans and banners: Reform Belum Selisai (reforms did not end).

Translation often requires symptoms. Indonesia’s provocation has found them in colorful colors. Opium’s green vest has become a short hand for the wrath of the working class, the color has already been charged with meaning in Indonesia, where the Green Jackets have come to represent the extraordinary flammable economy.

The second symbol, pink, emerged more unexpectedly. A woman from a pink hijab, who was standing in her hand before the gates of Parliament, was photographed and was broadcast in the networks. She came to represent the house – and the women’s labor – the rotten the rot. Pink indicated courage, not gentle, and the broom became a powerful weapon like any molotov cocktail. “The brave pink, the hero Green,” journalists began to call the pair, and social media turned them into the language of resistance: memes, avatars, graphty and banners, which are repeating both colors as railing screams.

Unlike some of the leaders who stirred the spirit, the Indonesian movement has described a set of demands. Packed online as “17+8”, including 17 quick calls and 8 structural improvements. Small -term targets are straightforward: Leave the facilities behind, launch an independent investigation on police violence, release detainees and keep the army out of control of the crowd. The purpose of long -term demands is to intended deep surgery: restoration of the legislature, seizing the assets of corrupt officials, reforming police and increasing the concerns of weak workers. This platform was collected by student groups, promoting it by labor unions by sharp and influential. In this period when there is often a lack of attention, it gives 17+8 harmony – a document that can be held against the government, a yard stick by which it can be measured whether privileges are real or cosmetic.

No one can imagine that protesters will march their demands in a straight parliament. Instead, the political parties find themselves frozen, treated with such humiliation, which causes it to flare.

The reasons are layered. First, the legal status: the DPR itself is seen as the zero of the scandal, which is the heart of the elite argument. Secondly, many Indonesian people think that business and political elites work in a closed loop, reinforces each other while ordinary people are left behind. Third, distrust: Students and lower -level organizers fear that engaging parties will only reduce the fast, cooperators and demands. Living on the streets is better to absorb in a system that they see that the disagreement is designed to make it ineffective.

Indonesia’s protests are not polite. Belbarkan DPR slogans – dissolve Parliament – Polse Pimonoh (police are killers). Others demanded the political system completely reset. The scenario of the sweep, repeated in the slogan for “sweeping the state”, and instead of growing reforms, the sense of cleaning cleaning itself. Unlike previous protests, focus on personalities, slogans of this movement target institutions.

Some observers have drawn harmony with 2024 students and quota protests from Bangladesh, which eliminated political assurances there. The echoing is clear: youth -led movements, which are categories of state violence, which grow through social media and are affected by women’s leadership. The two fought against the elite in the societies through inequality.

Yet Indonesia is different. The Bangladesh movement spread due to months of stirring, dozens of people, detained thousands of people and spreading detained and spitting political legal status. Indonesia’s crisis, though fatal, has not yet surrounded the entire system. Whether it depends on whether Prabu’s government behaved disturbing to suppress it or an account of embracing.

Unrest has spread across the borders in symbolic ways. Indonesian dyeing groups march in Berlin, New York and Melbourne. In Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian gathered outside the Indonesian embassy. In small gestures, ordinary citizens of Southeast Asia have ordered food for Indonesian delivery riders in solidarity. There is no evidence of state intervention, but there is a lot of evidence of regional sympathy. Indonesians recognize the globalization of the struggle against the exception of the elite abroad and neighboring elite.

Global media and analysts prepare it as a test for Prabovo’s youth. Reuters has called it the “biggest challenge” so far. The Financial Times sees deep economic dissatisfaction that can reduce development without leaving anything. The Associated Press reported serious human expenditure: seven killed, about 500 injured. Carnegie Endowment talks about calculating the common Indonesian residents and a collective elite. Credit agencies have warned that long tumultuous investors can promote and squeeze the state’s financial affairs.

Recently. What began as a problem for housing facilities has increased in the question of Indonesia’s stability and credibility.

If there is a way out, it is in concrete reform. First of all, there should be an independent investigation of the police casualties, the results of which the public is visible. Second, Perks should be returned not only temporarily but also permanently, with legal safety measures to prevent their silent return. Third, the army should withdraw from civilian policing. This demand is in the past Indonesia’s traumatic past. Fourth, to include students, workers and civil society, the conversation will have to move beyond the party’s elite. And finally, economic relief – subsidy, wage support, gig workers protection – will have to reduce material pain that fuel this anger. Without these measures, the concessions will look strategies and temporary. With them, Indonesia can have the opportunity to deepen its democracy.

Pink and green images are not just aesthetic choices. They are moral colors. The pink sweep reminds Indonesians of women who are not visible, and it has given rise to corruption from the nation’s house. The Green vest reminds them of the tumt workers, provides no security services, as long as one of them dies under the police truck.

Indonesia is the largest democracy in Southeast Asia, its economic engine and regional lunch. What happens there will resonate all over the region. If Jakarta can respond to this movement with real reforms, it can restore confidence in democratic accountability at a time when many people consider democracy hollow. If not, oppression will only be a generation of anger, and the broom will be more severe.

Protests clearly say: reforms have not ended. The question is, does the government dare to complete the work?

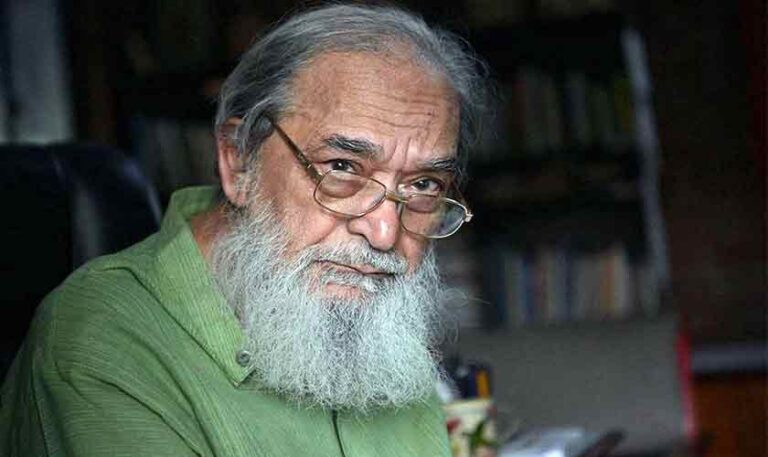

tHe is a professor at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at the Beacon House National University in Lahore.