#vanquished #history #Political #Economy

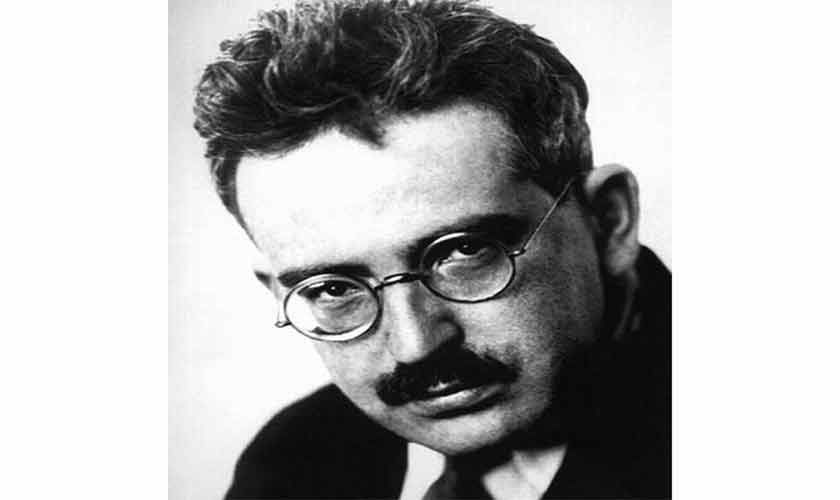

History (1940) on philosophy (1940) is a dense, poetic critic of both the traditional historical and Orthodox Marxism, written in the shadow of fascist expansion and personal danger. Challenging the idea that history is a linear development toward human development, Benjamin claims that this idea of ”progress” hides the violence and suffering by the oppressed. While highlighting Paul Kali’s Angeles Novos, they present history not as a series of victory, but as an endless pile of debris, each generation is buried under the last ruins. Benjamin has also criticized the “scientific” historical material of his time, and has attributed it to the “mechanical Turkish automaton”-apparently operating itself, but in fact relies on hidden theology. He suggests that any attempt to understand or change history is theology, especially Christian thinking, an inevitable, even necessary, power.

Instead of seeing time empty and permanently, Benjamin introduced the concept of Christian time – a sudden historical breakdown moments when the past becomes necessary. He says that the role of historical materialist is not to mention the past “as it was really”, but rather to seize forgotten or suppressed memories in moments of crisis, aimed at stopping stagnation and relinquishing the past. Influenced by the concept of Jewish concept. Benjamin’s vision is a ransom rather than prejudice: revolution is not inevitable. It is necessary to fight. History should be saved from the story of winners.

History is considered as a long -time winner. The rulers, the winners, the dominant powers have written on their own version pills, communications and archives of the past. The voices of the defeated are often quiet. Nevertheless, as Walter Benjamin argued, the winner’s legacy never ends. If history is written in favor of power, it is also disturbed by memories of discomfort, martyrdom and resistance. While highlighting the vision of Benjamin’s history, the author argues that some of the most decisive turning point in human civilization did not by the winners but by victory – whose outward defeat became the seeds of sustainable change.

Benjamin wrote during the dark night of Europe, as fascism marched throughout the subcontinent. Against the satisfactory belief that history moves towards a straightforward development, it issued a warning: every so -called “victory for civilization” raises the hidden wounds of those who were crushed on the way. He wrote, “There is no civilization document, which is not a barbarism document simultaneously.” For this, history, as commonly told, is the story of the winners – king, kingdoms, generals. The suffering of the oppressed is buried under their monuments.

But Benjamin was not convinced that the story ended there. He called on us to “brush a history against grain.” That is, instead of reading the past, the way it is commonly presented – smooth, linear, inevitable – we should look at the angle of those who lose it. When we do, we find that history is not a permanent march to move forward, but a broken region, which is full of cycles, losing possibilities and suppressed voices. The screams of the farmers, the dreams of the rebels, the sacrifices of the martyrs may not appear in the official dates, but they have not ended. They last longer sparks under the ashes, and wait for someone to take notice. When they are remembered, they can ignite the new struggle for justice and again. Orally stories are the best way to tap this flip of history.

The idea that defeat can be more powerful than victory. The ancient Greeks had already felt it in their tragedies. Heroes like Promotes were not a winner, but were personalities who suffered for the sake of others. Promotase, was always punished for stealing fires and giving it to humanity, was a criminal for the ancient. Modern thinkers like Carl Marx, he became “the best Sunnah and martyr” in philosophical piety – the symbol of rebellion and the courage to suffer for the truth.

The same contradiction is for Socrates. The purpose of his execution was to silence him forever. Instead, he ensured his infinite status. By choosing more death than a compromise, he left an image of integrity that would affect philosophy for centuries. As Kirkgard said, Socrates “gave birth to the dying philosophy for him.” His ‘defeat’ became the basis of philosophy.

History is much more than examples of such contradictions. Gladiator Spartaks, who led the massive slave rebellion against Rome, was hanged with thousands of his colleagues. The empire thought it had erased it. Nevertheless, centuries later, in the imagination of the revolutionaries, from Marx to Rosa Luxembourg, she was born again as a symbol of the fire of independence.

The screams of the farmers, the dreams of the rebels, the sacrifices of the martyrs may not appear in the official dates, but they have not ended. They spark under the ashes.

The crucifixion of Jesus Christ (this is peace) is probably a clear example of this. The Romans intended to have a brutal demonstration of humiliation and final form. Yet this clear defeat created one of the most sustainable religious and cultural traditions in human history. As Nutsche observed, “only where there are graves.”

There are more examples of this in the early modern era. John of Arc was put at stake, but today he stands as a symbol of a Sunnah and French unity. Jordano Bruno was burned alive for his courage to universe, Galileo humiliated his scientific discoveries. Nevertheless, their defeats cleared the path of victory for modern science. As Jacob Broarded noted, “Burning inquiry was not an innovation but a future.”

The Islamic tradition also protects the amazing examples of victory within the defeat. The most important of these is the testimony of Imam Hussein Ibn Ali (peace be upon him) in Karbala in 680 CE. In large numbers, he and his companions were martyred. Worldly, the reason for them was crushed. Yet the refusal to bow down before the oppression turned it into eternal symbols of courage. As Rabindranath Tagore reflected: “To keep the spirit of Islam alive, it was Hussein who stood up and sacrificed everything.”

Karbala’s story shows that some defeats live a longer life than clear victories. Centuries of centuries have looked at Imam Hussein’s sacrifice as a guidance for resistance. Edward C’s insight is appropriate: “History is written through corruption, but the defeated never refuses to describe its losses.” Karbala story is not a dead memory but a living present, which affects the movements of justice.

Benjamin offers a philosophical key why these defeats make so much difference to unlocking. He believed that every generation has what he has called “weak Christian power”. This is not a religious prediction but a moral responsibility: the ability to save past struggles and give them a new life at present.

Thus, the martyrdom of history – whether promotase, Socrates, Spartaks, Arc’s life, or other – are not just a person of regret. They, in his words, are “Christian time chips”. Each of them represents a path that may have changed the world but was violently blocked. Their defeat has an unrealistic future. When we miss them, we are not just honoring men. We are reopening the possibilities for which they stood.

This is the reason why Benjamin insists that historians should not be the only scope of victory. It is their duty to “take a memory because it shines in a moment of danger.” The task is to retrieve the hopes and sacrifices of the defeatists, move forward and prevent their struggle. In this sense, memory is a form of resistance.

Although winners command the official story, the conquerors often form a deep moral and cultural heritage of humanity. Their sacrifices destabilized the stability of power. Natshshe caught this contradiction with the sophistication of the characteristic: “Man should be measured by the enemies he chooses.” Those who fall before the powerful opponents often gain symbolic greatness that their conquerors deny.

Benjamin helps us reconcile with this contradiction. As written in writing may dominate the power, but the history of history and the remembrance history has been pursued by those who have yet refused to surrender their principles. Their defeat becomes the seeds of change, which offer that Benjamin is called “hope of hope”.

The author is a professor at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at the Beacon House National University in Lahore.