#smarter #Political #Economy

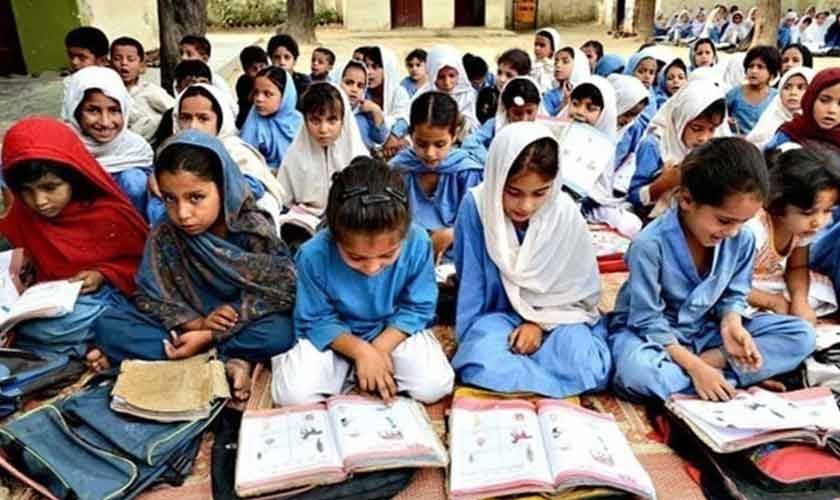

S Pakistan exposes their education budget for the fiscal year 2025-26, one of the financial desires created by the emerging image systemic barriers. Punjab and Sindh, together with more than 194 million people, who now educate more than 19 million children in 100,000+ schools. Nevertheless, about 17 million children are out of school. Critically, more than three out of four children in Pakistan are unable to read a simple phrase until the age of 10, which is a serious indicator of poverty learning that puts a long shadow on the milestone of any budget. The two governments have announced record education budget, Rs 812 billion (Rs 17.7 % of the total budget of Punjab) and Rs 654 billion (17.6 % of Sindh). But the deep question is whether these allocated access, improvement of measurement, and translating institutional flexibility.

Allocation shows that education remains a provincial priority. Yet, while shrinking help and financial barriers, the maximum challenge is not in the funding level, but the resources are planned and used in terms of strategies. These two provinces meet 15-20 % of the total public spending on education.For, for, for,. But now more precision, financial discipline and the system will have to provide more, with extensive performance.

Punjab, which has a population of 134 million, has 60,127 schools with more than 458,000 teachers and more than 15 million children have been registered, yet 9.6 million are out of school. Sindh, which has a population of 60.3 million, operates 41,158 schools, hires 162,000 teachers and educates 4.15 million children, while 7.6 million is out of school.

Over the past decade, the two provinces have extended education costs. Since 2010-11, Punjab’s budget has increased by 334 %, which has reached Rs 812 billion in 2025-26. Sindh has increased from Rs 109 billion to Rs 654 billion in 2012-13. Nevertheless, these additions have not improved access to access or learning. Punjab’s education share was reduced to 17.7 % in 2023-24.

In Sindh, the share of the education budget has been flat at about 17 %, which highlights the disconnection between costs and reforms. Only 31 % of schools have electricity and 57 % toilets. Punjab reports 99 % coverage, though the difference in quality and access remains. In both provinces, limited non -salty costs weaken the basic functionality, which, despite expanding the service supply, helps in a critical learning environment.

Punjab has increased its education budget by 17.7 % in fiscal year 2025-26, which has reached Rs 812 billion. Of this, 83 % are allocated for repeated expenditure and 17 % for growth. As a encouragement, about 60 % of the repeated allocation is directed to the basic and secondary education, which reflects the continued emphasis on the provision of basic education. The development budget shows the intention to reduce the transfer barriers, 43 % is allocated for secondary and higher secondary education, which reflects investment in girls’ education and school upgrades.

Sindh’s education budget has Rs 654 billion, which marks a 29 % increase over the previous year. This distribution is a mirror of Punjab, which is allocated for 85 % of the budget repeatedly for expenditure and 15 % for growth. In particular, Sindh’s development budget has increased by 139 %, which is primarily driven by infrastructure expansion and school recovery. However, the transparency of the budget remains a concern. More than 86 % of Sindh’s development allocation has been classified under the headline of ordinary ‘others’, which covers flood recovery, decentralized administration and miscellaneous care.

In terms of active ranking, Punjab allocates about 59 % of its total education budget, including government agencies and low -cost private providers, including PEF and PEIMA. Higher education is relatively modest part, for large -scale public colleges and administrative expenses.

Sindh’s budget reflects more dispersed structure: 54 % supports basic and secondary education and 19 % goes to higher education. The remaining 27 % are divided into exam boards, teachers’ training institutions and independent institutions. This dispersion of funds in many institutions reflects more – the point of view, but reduces the alignment between financial allocation and learning results.

If Punjab and Sindh have to transform education as a vehicle to tackle poverty, advance involvement and enable economic growth in learning, they will have to adopt a financial strategy that anchored evidence, results and system performance.

Both provinces face a common challenge: structural imbalance between repeated and development costs. And within the development budget, permanent use.

Despite the increase in growth in the financial year 2023-24, the implementation remained uncomfortable. Punjab used about 75 % of its development budget. Sindh spent only 65 %, which continued to reduce a decade -long trend. Although Punjab has shown good use in recent years, it should be seen against the previous history of weak passion. On the contrary, Sindh has struggled with permanent development, which reflects the low cost rate rate of the company’s barriers and scattered plans.

These figures highlight the problem of a wider governance: Effectively spending the system has increased rapidly more growth than the system’s capacity. Fund releases, barriers to purchase and delay in the district level limited preparation of the project. In such landscapes, the maximum amount often increases the balance rather than translating into the results.

At the same time, relief land is changing, traditional development aid agreement and more emphasis on mobilizing domestic resources. As financial barriers intensify, the performance of development costs, not only its quantum, has become an essential priority for both provinces.

The Education Commission emphasized a basic education: Maximum amount will not only fix education, it spends so much. Punjab and Sindh have begun promising reforms, including school -based administration and initial grade interference. Yet many people go away from the budget, depending on the donor or poor. It weakens the continuity, reduces dizziness planning, and limits long -term effects. Anchoring such reforms in the basic budget with clear lines and performance measures can eliminate the gap between ambitions and delivery. Strategic public spending has to be prepared to change the education system to change, and each rupee has to link the results that in fact improve learning.

Analysis highlights a structural fact: Pakistan’s education budgets are high in volume but healthy is weak. The provinces fund the system and institutions rather than the consequences. Budget systems reward head count and infrastructure extension, but not necessarily improve learning, participation or maintaining.

If Punjab and Sindh make education as a vehicle to tackle poverty, advance involvement and enable economic growth in learning, they should adopt a financial strategy, which is anchored in evidence, results and system performance. It faces several strategic shifts. First, the practical allocated amount should prefer basic education, girls’ education and secondary transfer, using separate data to guide equity -based planning. Second, development costs need more discipline. Project pipelines should reflect preparation, phased timelines and clear performance indicators. Connecting the fund release and delaying the cost of spending can be delayed.

Third, models based on modern finance, public private partnerships, education bonds and results can complete the basic budget, but require strong regulation and institutional capacity. Fourth, teaching in the budget structure through dedicated provisions for teaching, diagnosis and inclusion can be embedded in the budget structure. Finally, performance across the system has to be improved. Budget should be linked to performance, shopping should be smooth and government level harmony should be increased. Spending audits of reviews and results can ensure that investment access, equity and measurement benefits are available.

The education budgets of Punjab and Sindh indicate their commitment to maintain education expenditures between financial support. However, in the current climate, the maximum amount will only make a difference when it is spent more effectively. Without a strong link between allocating and learning differences and reliable improvement in use, it will have a large but slight influence in the budget size.

The question is no longer we are spending enough. This is whether we are spending wisely. Moving from access to learning; From policy to performance; And from desire to success, the provinces should now not only make the education budget big but also make it more smart.

Note: This is the second in a series of three parts of education financing. First conducted the federal budget. The next will focus on Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

Ahmed Ali is affiliated with the Institute of Social and Policy Science. It can be arrived at Ahmadaley@gmail.com