#possibilities #Sinocentric #world #order #Political #Economy

s In the Western leadership, global domination begins to show signs of decline, a growing conversation around the emerging global discipline. The rise of China, in addition to the power in the Indian Ocean, is forced to re -evaluate global governance.

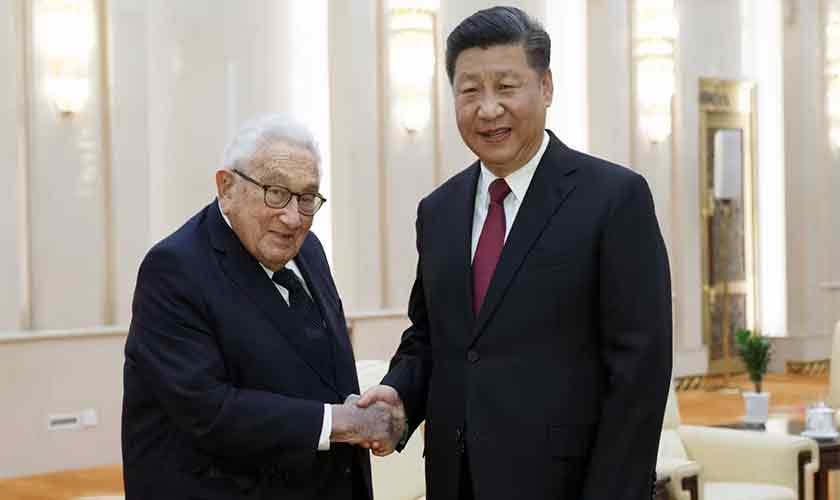

Whether it is a straightforward power transfer or deep cultural change remains an open question. Henry Kissinger cautiously detected philosophical and strategic traditions under his deep reflection book, China, under the state ship of China, presented a picture of a force that prefers patience, continuity and ambiguity.

On the other hand, thinkers like Samuel Huntington have argued that China’s restoration is part of a broader “civilization collision”, in which the sink civilization will try to emphasize itself against Western domination. Peter Nolan has added another dimension, highlighting how the West primarily misunderstood China’s political economy from the old binary of the market. Nolan emphasizes that the Chinese model is not merely active, but also theoretically connected in ways that have failed to understand the West.

The rise of China invites a serious inquiry into whether a Chinese -based global discipline is proud, and what can mean for countries that are traditionally operating under the scope of global power centers. Pakistan, geographical politically important but permanently unstable, is a great case study. The central question is whether China can engage with Pakistan in the way China and its allies have done in the past.

This author believes in the importance of an important decisive geography in forming any country’s foreign policy. The answer to this disturbing question is thus complex and depends on changing assumptions about strength, influence and patronage.

Based on the theory of realistic international relations, especially Robert Gilpian’s power transition theory, it is clear that China’s climb challenges the United States’ longtime domination. The global system, once the polar after the Cold War, is now moving towards multi -faceted or bipolar, China is positioning itself as a central pole.

This is not just a challenge to a military or economic scale, but also one that forms a cultural and ideological legal status. Huntington’s cultural theory, which criticizes the exact lens, provides insight into how China sees itself. Peter Nolan’s analysis makes the image more complicated how the unique hybrid of China’s state control and capitalist integration has enabled it to expand global without adopting the Western Liberal Order.

An ambition to establish institutions like China’s Belt and Road Initiative, BRICS+ in the BRICS+ and the establishment of institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank suggests an ambition to regain global governance away from the principle of Washington’s centrality. Instead of universal values, China offers a highly practical theory of infrastructure contacts, strategic non -interference and international cooperation. Nevertheless, this vision, while theoretically lighter than Western liberalism, still keeps China firmly in the center, the peripheral states become nodes in a broad economic and logistics web.

In this matrix, Pakistan is in a unique position. On the one hand, its strategic geography makes it a valuable partner for China, especially as a transit of the Arabian Sea through China -Pakistan economic transit. On the other hand, Pakistan’s permanent institutional passive, economic delicacy and political volatility limits its ability to exceed the client’s state.

Although the CPEC has been won as a change plan, its benefits are disproportionately distributed, with Chinese firms and priorities often gain. Beijing’s view of Islamabad has been widely dealt with and plans: It is likely to see Pakistan as India’s counterweight, a buffer of unrest in Xinjiang and a logistics root – as the United States involved in Western Europe or East Asia during the Cold War.

Unlike the United States, which generally sets its support ideologically and is often engaged in the construction of institutions-even though mixed results-China’s patronage is interesting. In terms of security, China has provided military hardware and assistance, but it is unlikely that they unconditionally write Pakistan’s defense needs. Its security Calculus is explained by its own regional priorities, not the responsibility of unity.

Development, China does not try to export the governance model, nor does it invest in institutional reforms. It offers roads, ports and loans. Tools that can lead to growth, but also deepen dependence. This model is a level of the recipient’s capacity that Pakistan does not currently have.

Despite these obstacles, relations between China and Pakistan have gained a new power, especially as a result of the Pahalgam incident, which has briefly attracted regional attention to tension with India. The incident reminded both Beijing and Islamabad for their strategic alignment against a joint regional rival.

China’s diplomatic and post -certified promises are not only solidarity but also a strategic messaging: In the world of changing unity, Beijing is ready to save its allies when you do so, it fulfills its wider interests. For Pakistan, this event temporarily promoted in compatibility and assurance that China invests in bilateral relations, at least as long as regional enmity remains intact.

However, this new engagement should not be mistaken for a fundamental change in the nature of the relationship. China’s Calculus mainly served itself, and has a support. It is not a long -term development vision for Pakistan but a strategic hedge. Contrary to US ideological patronage, China’s support will not attract Pakistan to democratic reforms, institutional stability or social development. If anything, it enables the stagnation, unless the stagnation disrupts China’s regional agenda. This is important because the possibility of social and political reforms within Pakistan does not appear.

A Chinese -based global poem can really be born as the West, which faces internal crises and geographical political fatigue, i’tikaaf. This new order will be clearly different. It will not give liberal values nor offer a deep contribution. Permanent states like Pakistan have to be careful with caution. This opportunity is real-Geo Economic Compatibility, Strategic Alignment and Access to the Chinese Capital. Similarly, there is a danger: dependence, loss of sovereignty and backwardness if internal reforms remain vague. Pakistan is at a crossroads. Without internal change, its role is not just a stakeholder in the China -based world, just the risk of drains. In such a scenario, its destiny will be found not in Islamabad, but in Beijing.

The author is a professor at the Faculty of Liberal Arts at the Beacon House National University in Lahore.